Jonathan Mossberg is a descendent of a nearly century-old, leading American arms manufacturer, so a couple of months ago when his 21-year-old daughter refused his gift of a handgun because she was afraid an attacker might take it away and use it against her, he realized he'd found a key demographic for a smart gun.

Sixteen years earlier, Mossberg had been working at his family's namesake company, O.F. Mossberg & Sons in North Haven, Conn., which was founded in 1919 by his great-grandfather Oscar. The company had previously attempted to develop a shotgun that could be fired only by its owner, but the technology proved unreliable so the younger Mossberg set himself the task of developing a more sophisticated weapon.

As the platform, he chose the company's Model 500, a 12-gauge shotgun in production since 1961. Mossberg's goal was to create a gun that could pass a U.S. military use standard (also known as Mil-Spec), while also preventing anyone other than its owner to fire it. And he succeeded -- 16 years ago.

"My patent attorney thought I had the next dotcom, but focus groups said they weren't interested in circuit boards in guns," said Mossberg, who is 51.

However, "half a generation later" Mossberg found technology-savvy consumers who were ready.

"Kids are living on their cell phones; reliability of the circuits boards are not an issue with them. The cops love the product," Mossberg said.

But the picture's still not completely rosy. Like other innovators who've developed smart gun technology, Mossberg found seed money difficult to come by for his iGun Technology Corp. and its iGun. Still, he managed. Between his family's arms business and a machining business he later opened, he was able to put about $5 million into developing the weapon.

"The market now is not in shotguns; there's a market in handguns because that's a billion-dollar market," Mossberg continued. "We're going to jump to the handgun as soon as we raise enough money to do that... but we're tapped out."

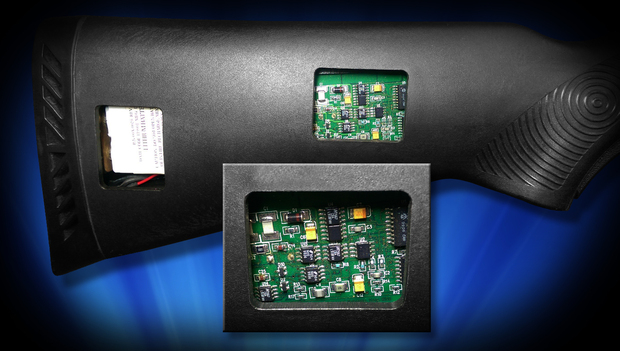

The circuit board inside the iGun's stock is from iGun Technology Corp., also the weapon's maker. The processor recognizes a signal from an RFID chip in a shooter's ring and unlocks the gun's trigger.

Pushback against smart guns is common from some gun owners and advocacy groups. The fear is two-fold. For one, gun owners are concerned that adding technology to a weapon's time-tested functionality could cause the gun to fail when it's most needed. Second, there's fear that once smart guns are available, states and the federal government will mandate them. That fear is not without merit.

The smart-gun development community, however, is virtually in unison in decrying government mandates for their technology. Mossberg and other say smart guns are not for everyone, nor do they fit every purpose. For example, while smart-gun technology may save a police officer or soldier from having their weapon used against them, a hunter has little need of a fingerprint scanner or radio frequency identification (RFID) chip in his weapon.

When it comes to the technology affecting reliability, Mossberg understands that some smart guns will be more reliable than others. But with the right technology -- especially today's advanced microelectronics -- they can be just as reliable as any standard weapon.

iGun Technology Corp.

iGun Technology Corp. The iGun ring with an RFID chip. An LED light in the stock shows when the weapon is locked or unlocked.

"I came from the gun industry. I know what reliability means. I'm a gun owner. I'm an NRA member. A gun needs to work when you need it to work. You don't want to swipe your fingerprint and have it say, 'Please try again.'" Mossberg said. "My goal with my engineers was to build a gun as reliable as the most reliable gun in the world, which was the Mossberg Model 500."

For the iGun, Mossberg chose a ring with an RFID chip in it to send a signal to a circuit board in the shotgun. The RFID uses a low magnetic frequency that requires a shooter's hand to be properly oriented to the gun's trigger, and the chip transmits its low-frequency signal only a couple of millimeters. Once someone wearing the ring grabs the shotgun, the circuit board activates two tiny motors that unlock the trigger. The entire process takes less than a quarter of a second, Mossberg said.

The company's first ring was the size of a Superbowl ring -- in other words, huge. But now, "with this current chip... we're talking technology that's now the size of a grain of rice. There's no electricity. There's a battery in the ring. It's waterproof," he said.

Mossberg said his iGun shotgun is only a prototype and his goal is to create a line of smart pistols.

In 2013, Mossberg's iGun won a first place innovator's award from the Smart Tech Challenges Foundation, an organization founded by Silicon Valley angel investor Ron Conway for the purpose of promoting gun safety technology. From a $1 million kitty, the Foundation awarded Mossberg a $100,000 development grant. Along with Mossberg, the Foundation has awarded 15 development grants to innovators, such as Tom Lynch who put a fingerprint scanner on an AR-15 assault rifle, Robert McNamara whose guns also use RFID chip technology, Omer Kiyani, who created a biometric gun lock and Kai Kloepfer.

Kloepfer, who founded Biofire Technologies, began developing his smart gun four years ago when he was only 15. Two years ago, his fingerprint-reading smart gun won the Colorado teen a $50,000 grant from the Smart Tech Challenges Foundation. Prior to that, he'd also won top honors for his smart-gun engineering project at the 2013 Intel International Science and Engineering Fair, where he was one of only 34 award recipients out of seven million high school students who entered from around the globe.

The 19-year-old is now a freshman at MIT, and he recently completed his latest prototype of a fingerprint reader embedded in a semi-automatic pistol; this one uses a Glock Model 22 .40 caliber handgun. Kloepfer inserted the stamp-sized fingerprint reader into the gun's hand grip; a circuit board and lithium polymer battery allow the sensor to read pre-authorized fingerprints and unlock the gun.

A prototype weapon from Biofire Technologies shows the circuit board embedded in the pistol grip.

The fingerprint sensor is ergonomically placed at the top of the handgrip. When a right index finger is inserted into the pistol's trigger guard, the hand's middle finger naturally comes to rest atop the fingerprint reader.

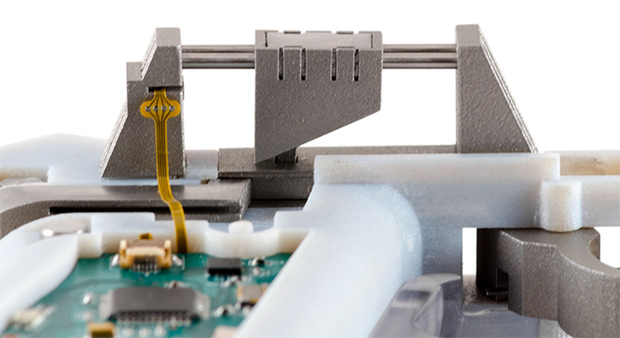

But it was Kloepfer's unlocking mechanism that made his smart gun unique among others. It uses a special wire -- an actuator-shaped memory alloy -- that when heated via a command from the gun's circuit board, contracts and unlocks the trigger mechanism. There are no motors, which would require a lot more of handgun's tiny real estate.

The fingerprint reader on an early prototype from Biofire Technologies.

A USB port on the bottom on the handgun can be used to charge the weapon's lithium-ion battery, which Kloepfer said should last at least a year.

An early prototype of the weapon can be seen in this YouTube video posted last year.

Along with perfecting the electronic-mechanical interface, Kloepfer's greatest challenge to date has been reducing the time it takes the for gun to unlock -- currently 1.5 seconds. "I expect to see that decrease to under half a second on a production model," he said.

The trigger actuator mechanism in one of Kai Kloepfer's early prototypes.

Unlike many of the smart guns produced in the mid- to late-2000s and that used decade-old processors and other outdated technology, today's weapons are taking advantage of the latest microprocessors and biometrics readers. For example, Kloepfer's fingerprint reader comes from Fingerprint Cards AB, a Swedish tech company whose biometrics are used in Google's new Pixel smartphones, and the circuit board sports an ARM Cortex A4 processor.

"We're not talking about electronics that launch men up to the space station or Mars or even in an everyday airplane with a few hundred people on board," said Margot Hirsch, president of the Smart Tech Challenges Foundation. "We're talking about ruggedizing and miniaturizing electronics, but not under as rigorous conditions as we see in other markets. This technology is not new."

Hirsch pointed out that no one smart gun technology is going to fit all gun owners' needs. For example, police and military who often wear gloves may not choose an embedded fingerprint reader that would fit the bill for a home defense weapon.

"I think a gun owner would pick a smart gun technology depending on the purpose of the gun," she said. "Think of this in relation to when the Apple iPhone first came out. The first generation of smart guns will appeal to those who are comfortable with the new technology. Then there's going to be a segment of the market who'll not be comfortable."

However, the technology most likely has a place in a nation that allows millions of citizens to own a firearm legally. For example, suicides are the leading cause of firearm death and most often those guns are owned by a family member or friend. If those firearms had biosensors, their use could be limited.

A smart-shotgun prototype from TriggerSmart, a company founded by Tom Lynch, who won a $100,00 grant from the Smart Tech Challenges Foundation. The smart gun uses the latest RFID and wireless technologies, and only a shooter wearing a corresponding ring can fire the weapon.

Hirsch, whose fiancé owns a gun, refuses to buy one herself because like Mossberg's daughter she's "terrified" it could be wrestled away from her by an attacker. "If there were smart guns, I'd probably own a gun because I'd never be concerned it would be used against me," she said.

![Get Ready for the Bot Revolution - illustration by Richard_Borge [SINGLE USE/Computerworld]](http://core2.staticworld.net/images/article/2016/09/cw_bot_revolution_illustration_by_richard_borge_2016_single_use-100684307-carousel.idge.jpeg)