Soon we may have a space-based optical backbone capable of transferring data 1.5 times faster than Earth-based terrestrial fiber, now that the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) has given LeoSat the go-ahead to start its build-out.

Moving “large quantities of data quickly and securely around the world, is fast outpacing the infrastructure in place to carry it,” says LeoSat in a press release announcing its FCC market-access grant last month. Upcoming LeoSat, will be a “a backbone in space for global business,” the company says.

It, along with SpaceX, Kepler and Telesat, requested permission the FCC to roll out non-geostationary satellite orbit (NGSO) satellite constellations. All four organizations were given approval (pdf) in November.

The Florida-based LeoSat says it’s planning a constellation of low-orbit communications satellites starting in 2019. It will be pitching its satellite-to-satellite laser-driven bandwidth at mobile network operators for 4G and 5G backhaul, enterprise and government for global networking, and particularly banks and others for transactions.

Verticals such as oil and gas are other prospects, it says. Remote data users, such as those in the mining and the maritime industries, will get “significantly more bandwidth” than is available now, the company claims.

Transmission speed of up to 5.2 gigabits per second

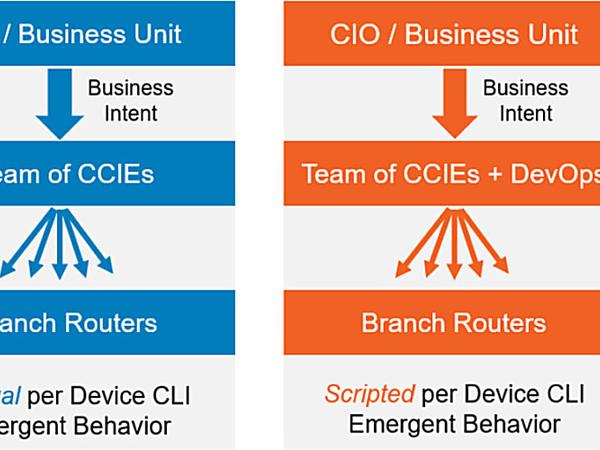

Optical laser links will run between networking router-like satellites in a Low Earth Orbit (LEO), much closer to Earth than traditional geostationary orbit (GSO) satellites. In fact, the LeoSat constellation is planned to be 25 times closer than GSOs and five times closer than Medium Earth Orbit (MEO) satellites. Speed delivered will be up to be up to 1.2 gigabits per second ordinarily, maxing out at 5.2 gigabits in some cases, it reckons.

Interestingly, and something that’s not seen in older satellite systems such as GSOs, is that latency is promised to be significantly lower than traditionally seen. LeoSat is promising only 20 millisecond roundtrip delays.

That latency-reduction is in a major part due to distance. A classic GSO satellite can be about 22,000 miles above the surface of the earth, for example, and those distances from sea level to the satellite historically have been a major contributor to slow round-trip times.

A round-trip to a GSO can take 500 milliseconds, Ronald van der Breggen, chief commercial officer of LeoSat, writes in December’s Asia-Pacific Satellite Communications Council’s magazine.

GSO satellites have always been geared towards providing high-quality video, not data, he says, and for that medium, latency hasn’t mattered too much. Since data-load is now taking over big-time from video, new, faster technology is proposed. That can be provided, in part, by bringing the satellites closer to Earth. LEOs will deploy at only 870 miles above the Earth.

“Closer is better,” LeoSat says.

Satellites, in theory, are good for data as the world becomes more information-driven—gaps in pipes to remote places, and countries even, need quickly filling. There are other advantages to satellite over ground networks, though, and that’s that because when you connect the spacecrafts using lasers, as in its planned constellation, throughput is significantly faster than fiber, LeoSat says.

“Bits travel faster in free space than in glass fiber cable,” it says. Thus, by taking advantage of free space physics, along with the aforementioned proximity now to Earth, and by copying common network topographies and ideas used in ground-based data networks rather than video networks, you’ve got a compelling data product, LeoSat says.

“Satellites have now become routers,” the company said in a caption to a YouTube promo video in 2017.