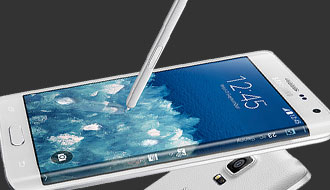

Rendering of SRP's DataStation, a home for data centers on its grid

A power company in Arizona is building a data center that plugs directly into its high-voltage transmission grid, a first of its kind project that could cut the cost of providing compute services and avoid the need for unsightly new power lines.

Data centers, like most other buildings, typically connect to the grid far downstream from where power is produced. But the utility in Phoenix, called Salt River Project, is building a data center at one of its power stations directly on top of a high-voltage transmission line.

That has a couple of benefits, said Clint Poole, a manager with SRP's telecom division. The power supply is far more reliable close to where it's produced, meaning the data center should be able to operate without the need for a costly generator for backup power.

"When you take a data center and put it on the bulk transmission grid, you not only give it access to more power, you give it access to more reliable power, and also better quality power," he said.

It could also help SRP to meet the increasing power requirements of data center customers without needing to build new transmission lines. Those cables strung high overhead are costly and often meet strong resistance from nearby residents.

"When people say 'not in my back yard,' transmission lines definitely apply," Poole said.

SRP is building the data center for an unnamed customer as part of a pilot project with BaseLayer, a company that provides modular computing equipment that can be deployed outdoors in shipping containers.

The data center won't literally plug into the transmission grid, which carries a hefty 230 kilovolts of current, compared to tens of kilovolts further downstream. Instead, SRP is building a "docking station" with several transformers that will step the current down to a usable level.

If the project is successful, BaseLayer will work with other utilities to try to spread the idea around the country, said BaseLayer CEO Bill Slessman.

It's not a difficult project from a technical perspective, Poole said. The hardest part was convincing an institution as risk-averse as a power plant to experiment with such a new idea.

"Concepts like this that make so much sense will most likely be replicated," he said.

SRP expects to start bringing the data center online in the first quarter next year. If it's successful, future data centers could be built for enterprise customers, or for collocation providers that sell computing services to other businesses.

It's not clear yet how great the savings will be, but they could be substantial. The electrical supply is so reliable at a power plant that customers can avoid buying not just the generator but another piece of backup equipment called an uninterruptible power supply, Slessman said.

The power plant also saves money, by avoiding the need for new transmission lines, so it will entice customers to locate there with aggressive rates for power.

SRP is well suited to the project because it's also a water utility and a fiber optic service provider -- both of which data centers need. Other power plants might not be as well positioned try out the idea. And BaseLayer had to work closely with SRP to get its Edge data center equipment certified for use on the transmission grid.

Still, if other utilities see a way to cut significant costs, they're likely to sit up and listen.

Data centers are huge consumers of power. They account for an estimated 2 percent of all U.S. electricity use, and the figure could balloon to 20 percent by 2030, according to a 2011 estimate from the Electric Power Research Institute.

James Niccolai covers data centers and general technology news for IDG News Service. Follow James on Twitter at @jniccolai. James's e-mail address is james_niccolai@idg.com