Miniscule robots that can jump and crawl could soon be added to the industrial internet of things’ arsenal. The devices, a kind of printed circuit board with leg-like appendages, wouldn’t need wide networks to function but would self-organize and communicate efficiently, mainly with one another.

Breakthrough inventions announced recently make the likelihood of these ant-like helpers a real possibility.

Vibration-powered micro robots

The first invention is the ability to harness vibration from ultrasound and other sources, such as piezoelectric actuators, to get micro robots to respond to commands. The piezoelectric effect is when some kinds of materials generate an electrical charge in response to mechanical stresses.

Researchers at Georgia Tech have created 3D-printed micro robots that are vibration powered. Only 0.07 inches long, the ant-like devices — which they call "micro-bristle-bots" — have four or six spindly legs and can can respond to differing quivering frequencies and move uniquely, based on their leg design.

Researcher say the microbots could be used to sense environmental changes and to move materials.

“As the micro-bristle-bots move up and down, the vertical motion is translated into a directional movement by optimizing the design of the legs,” says assistant professor Azadeh Ansari in a Georgia Tech article. Steering will be accomplished by frequencies and amplitudes. Jumping and swimming might also be possible, the researchers say.

Self-organizing micro robots that traverse any surface

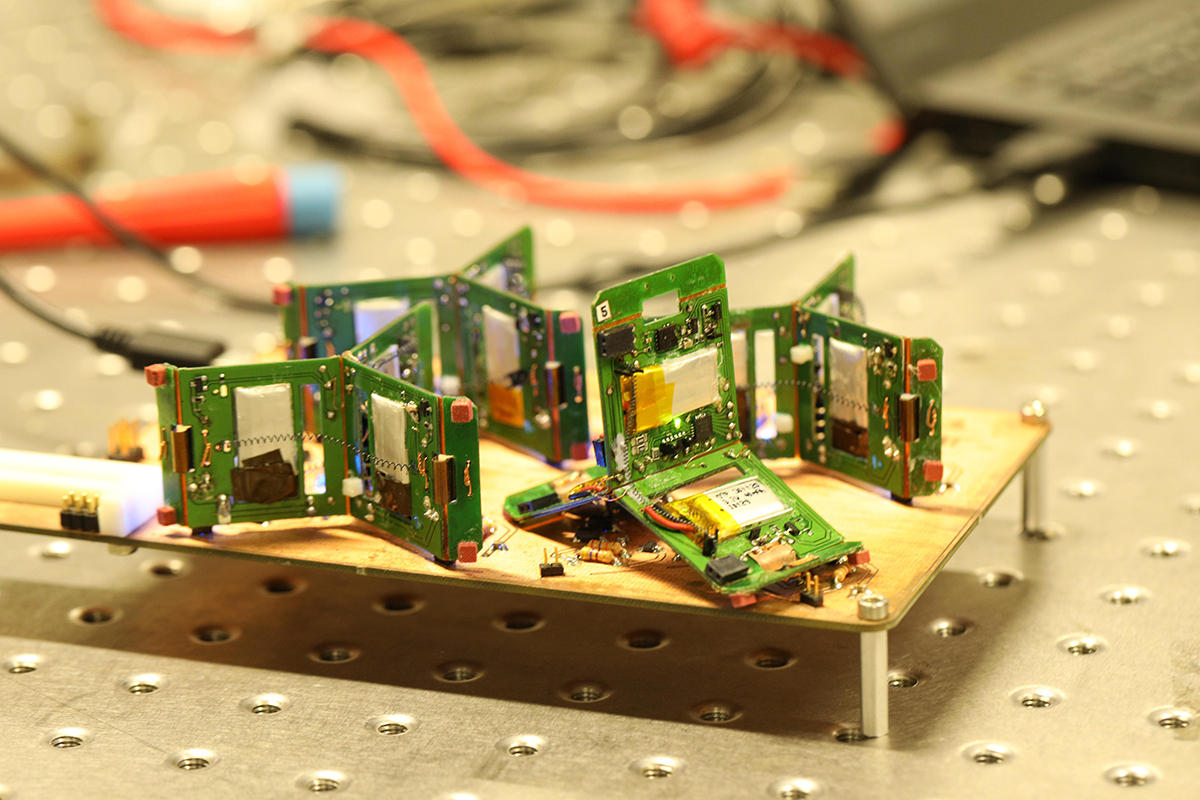

In another advancement, scientists at Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL) say they have overcome limitations on locomotion and can now get tiny, self-organizing robot devices to traverse any kind of surface. Pushing objects in factories could be one use.

The robots already jump, and now they self-organize. The Swiss school’s PCB-with-legs robots, en masse, figure for themselves how many fellow microbots to recruit for a particular job. Additionally, the ad hoc, swarming and self-organizing nature of the group means it can’t fail catastrophically—substitute robots get marshalled and join the work environment as necessary.

Ad hoc networks are the way to go for robots. One advantage to an ad hoc network in IoT is that one can distribute the sensors randomly, and the sensors, which are basically nodes, figure out how to communicate. Routers don’t get involved. The nodes sample to find out which other nodes are nearby, including how much bandwidth is needed.

The concept works on the same principal as how a marketer samples public opinion by just asking a representative group what they think, not everyone. Ants, too, size their nests like that—they bump into other ants, never really counting all of their neighbors.

It’s a strong networking concept for locations where the sensor can get moved inadvertently. I used the example of environmental sensors being strewn randomly in an active volcano when I wrote about the theory some years ago.

The Swiss robots (developed in conjunction with Osaka University) use the same concept. They, too, can travel to places requiring the environmental observation. Heat spots in a factory is one example. The collective intelligence also means one could conceivably eliminate GPS or visual feedback, which is unlike current aerial drone technology.

Even smaller industrial robots

University of Pennsylvania professor Marc Miskin, presenting at the American Physical Society in March, said he is working on even smaller robots.

“They could crawl into cellphone batteries and clean and rejuvenate them,” writes Kenneth Chang in a New York Times article. “Millions of them in a petri dish could be used to test ideas in networking and communications.”